The biggest elections

around the world

India: The price of influencers

In India, the world’s biggest elections took place across seven weeks from April. The winner was announced in early June – and the results were shocking.

The incumbent, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), was expected to win a majority for a third term. Although Prime Minister Narendra Modi did secure a third term, the BJP failed to achieve an outright parliamentary majority, falling well-short of its 370 target in the 543-seat lower house of parliament (Lok Sabha).

Yet the party spent significantly more on advertising on Meta compared to its opposition, according to Who Targets Me. In total, over the course of the campaign, the BJP spent more than $4.3m (INR353.9m) on the social media platform, increasing its spend vastly in the few weeks before polls opened on 17 April. In comparison, the Congress party spent just $1.4m (INR118m) on Meta.

But what played a crucial role in India’s election was the use of influences on social media.

Vinay Deshpande, co-founder of Rajneethi, a political management consultant, told the BBC, that previously they have helped opposition candidates win an assembly election through pushing out content via a curated list of local influencers with active followers. It can really help turn the vote in favour of a particular candidate.

"Social media content is powerful and can influence the way a person feels about an issue. It gives social currency to a belief or opinion – but this can lead to a lack of critical thinking about an issue," he adds.

In terms of pricing, at the lower end of the scale, influencers can charge around $24 (INR 2,000) a day; while at the top end, it can be anything around $6,000 (INR 500k) – which is what the BBC reported some political parties and election management firms had offered influencers. This is the equivalent to a month’s salary for someone in a senior management role.

UK: Which party is telling the better story?

At the time of writing, the UK is in the midst of a general election, with voters heading to the polls in a week's time. It means the two major parties – Labour and the Conservatives – are at the height of their campaign activities.

The UK has strict rules around how much parties spend on campaigning, how they are financed as well as where they can advertise. British political parties have been legally banned from buying TV ads ever since commercial television began in 1955 – the idea being to stop wealthier parties buying their way into voters’ homes.

However, the regulation – last updated in 2003 – only applies to traditional, linear TV and does not include streaming services or platforms, such as YouTube or videos via social media channels. Channel 4 and ITV – two of the biggest UK broadcasters – have chosen to apply the ban across its on-demand services

That leaves social media. And it seems that the major parties all have a different approach to using the platforms to their advantage.

Labour vs Conservatives

Since parliament was dissolved, both major parties' paid social activities increased dramatically. On Meta, Labour has invested heavily across all its 513 active pages totalling £1.4m, spending £634k on its main party pages, according to data from Who Targets Me. This averages out to £2,999 per page.

In comparison, the Conservatives has funnelled two-thirds of their spend, which stands at £687k, into their main party pages, with the total across all 402 active pages at £982k. This works out at £2,442 average spend per page.

Made with Visme Presentation Maker

Click through to see how much each party has spent across Google and Meta

However, the biggest difference is the amount the two parties are spending on Google’s platforms. The Tories cumulative figure so far (until 15 June) stands at £69,142; whereas Labour is 10 times higher at £815,928. Both parties had a spike around 1 June – Labour at £84,349 and Conservative at £10,735 – and since then have had a steady spend.

But how does this spend translate into each of the respective parties' campaign strategies?

What is clear, Moseley says, is that “Labour has clearly invested heavily in video production”, whereas the Conservatives are using more “static imagery”.

“Labour was ready with a sophisticated and multi-faceted digital campaign from day one. Across both Meta and Google they have thousands of targeted ads across their party HQ channel and their leaders and members’ channels, showcasing policy, voter registration and mobilisation, a wide variety of exposure across Keir Starmer and shadow cabinet, content that reflects voter stories and more,” he explains.

Moseley describes Labour’s use of social media as a “overwhelmingly positive campaign, which focuses on change and future”. The party is using a refined “targeting machine” with 80-100 variations of ads, suggesting that each message is being targeted to a key battleground constituency.

James O’Flaherty, EVP of growth at B2B agency, Just Global, echoed Mosley’s thoughts, adding “how well Labour is using paid media channels”. He says: “We can see they are spending, and we can also (anecdotally) see there is a strong link between audience and message.

“There are a lot of old-man-vibes to a lot of the content running on platforms like TikTok – Ed Milliband being spontaneous and riding a bike through an empty street is high on the list of content to avoid!

“Some of it works, but I’m still yet to be convinced of the effectiveness of changing opinions for target audiences in these sorts of placements. What it undoubtedly does is raise awareness, and in those harder to convince or harder to motivate younger audiences, maybe that’s all the parties can hope to do.”

According to the ad data analysed, Labour is generally targeting their ads to men and women of all age groups, with those on Meta (Facebook and Instagram) and Google (YouTube) both skewing towards those aged 35 and above, most likely reflecting the age of the average platform user. While on TikTok, the party’s efforts are more organic and lean towards the younger demographic.

Keir Starmer needs YOU to vote Reform and give him a blank cheque.

— Vote Conservative (@ToryVote_) June 18, 2024

You’ve got a voice. Don’t lose it. pic.twitter.com/LIjU04BQ74

In contrast, the Conservative’s campaign is much more “tighter”, Moseley says, both on messaging and scale. He describes it as a “negative” campaign which attempts to discredit Labour policies as well as their leaders including Keir Starmer, Angela Rayner and Emily Thornberry.

Following the launch of the party’s manifesto on 11 June, there was a brief period where the Tories flipped to a more positive campaign messaging, focusing on the key benefits of their policies such as building more houses, scrapping ULEZ and tax cuts. But it has since gone back to attacking Labour’s ‘tax-trap manifesto’.

With regards to demographics, data from Meta and Google Ads shows that Tories have an incredibly broad approach, with much of their ads targeting men over the age of 45 – 55-64-year-olds being the favoured demographic on Meta.

There are very few ads that target the younger voters, Moseley points out: “We noticed in week two of the election campaign, a clear demonstration of this was the majority of national service social ads were being targeted only to ‘parent’ age votes – those over 35.”

And as polling day approaches, Moseley makes an observation on how the Conservatives have started using paid, which he says is a “really important development”.

“The Conservatives have started to launch separate pages away from party HQ that are spending big on anti-Starmer ads. These are labelled as being promoted by The Conservative Party, so fall within Facebook's election rules, but feel like quite a statement on how negative the Conservative brand currently is that they don't feel they can run these through central channels.”

Making each vote count

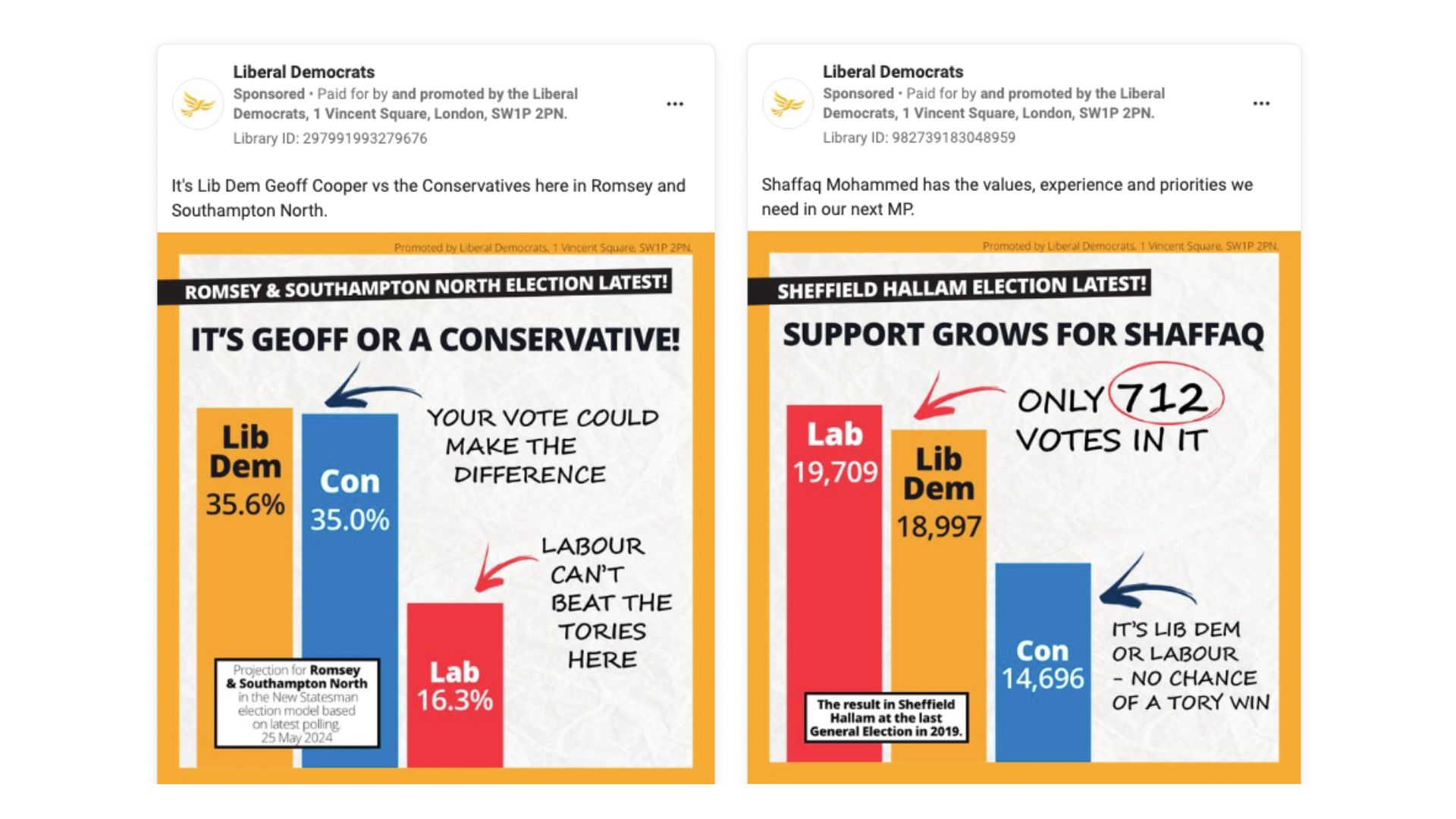

As for the other parties, O’Flaherty highlights Lib Dems “great mix of content”, where they have “produced what to me is the best piece of content of them all in Ed Davey’s very personal video story”.

The party is using a data-driven campaign that “puts candidates and constituencies, often with a smart creative showcasing voting figures… giving voters they need to make their vote count for the Lib Dems”, says Moseley.

There are 43 ads running on Meta, each personalised calling out the constituency and candidate running, suggesting the Lib Dems are targeting the key seats it can win. So far, it has spent £95,962 on Meta according to Who Targets Me, which is similar to Reform at £96,611– a late entrant into starting its paid social campaign.

Like the Lib Dems, Reform’s spend is targeted towards winnable seats with most ads having just three to four versions. Its campaign’s seem to take a page out of the “Brexit playbook”, says Moseley, describing them as “divisive” and like to “strike fires”.

How brands are harnessing the political momentum

A view from the author

It’s not unheard for brands to jump on the political bandwagon to shine a light on their campaigns. And this year is no different.

As O'Flaherty highlights, unlike the other general elections the UK has had in recent years, “this one feels like we already know the outcome”, so we’ve some brands having some fun with ads.

Uncommon Creative Studio’s Benjamin Golik created a “brilliant” fake ad, which went viral, and almost got mistaken for a real Labour OOH.

“This is bang on trend with the real and the unreal lines becoming more and more blurred in marketing today,” O’Flaherty says, “with people not knowing if ad stunts are real or CGI-fuelled, or even big brands using lookalike celebs to promote their wares, like we saw with Alexander Wang.”

His favourite, and mine too, is the one from Burger King, which placed ads on London buses with the strapline: ‘Another Whopper on the side of a bus: Must be an election’.

US: What can the industry expect

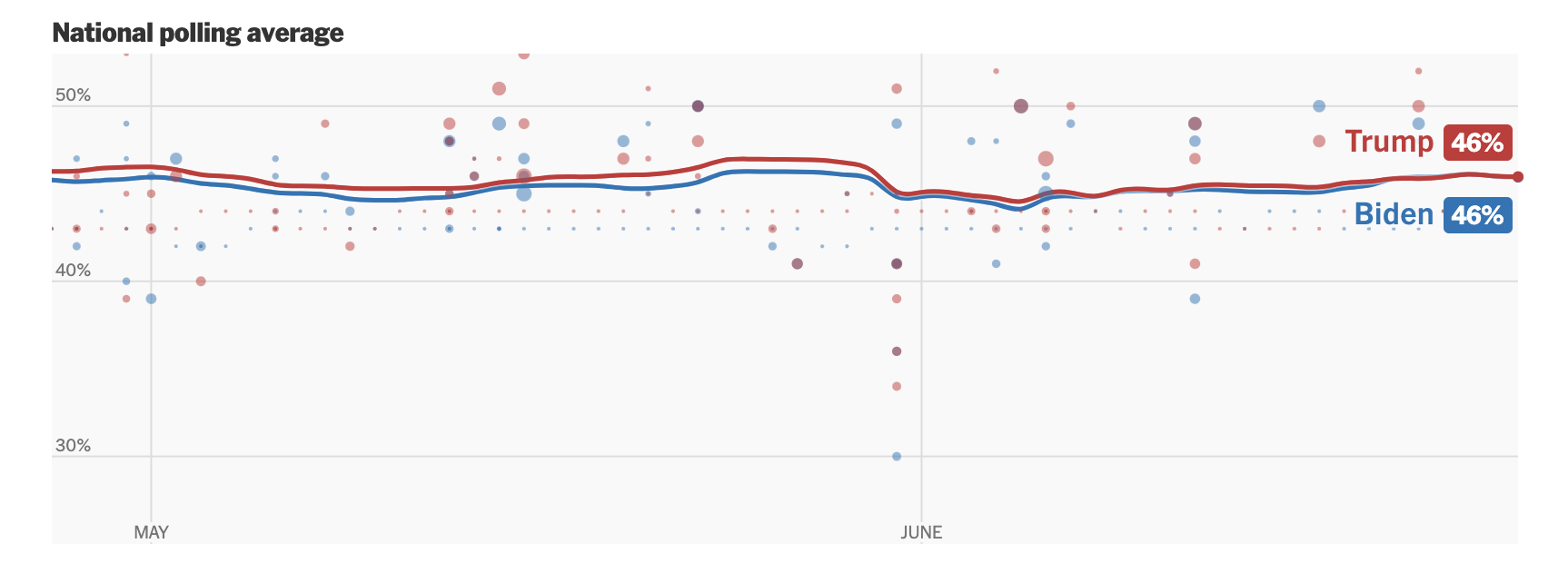

The US presidential election in November will see a rematch of the 2020 race between President and Democrat Joe Biden and Republican nominee Donald Trump. The New York Times’s current polls suggest a very tight race between the two nationally, with Trump taking a slim lead in the key battleground states: Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Nevada, Arizona, George and North Carolina.

Credit: The New York Times

Credit: The New York Times

While the elections are still five months away, with key primaries taking place across many states alongside a presidential debate, campaigning has well and truly begun – and social media is playing a vital role.

According to columnist and advertising analyst Brian Wieser, 46% of all political advertising is expected to be across digital platforms – up from 41% in 2022 and 32% in 2020. In contrast, TV is likely to only see 38% political advertising in 2024, compared to 42% in 2022.

He says: “If these figures play out, it will represent the first bi-annual election year where television was not the primary beneficiary of political advertising spending.”

With regards to social media, both the Democrats and Republicans saw an uptick in adspend across Google Ads in March and a spike in May, according to Who Targets Me. Both parties seem to be spending in waves, although the Democrats are starting to spend more on a daily basis.

In fact, since March 2024, Biden has spent almost double in adspend across Google – totalling $14.7m – compared to Trump at $7.5m (figure up to 15 June). And it’s a similar trend across Meta ads: $14.7m compared to just $2.3m respectively.

Made with Visme Presentation Maker

Click through to see how much each party has spent across Google and Meta

Alison Watson, EVP of Global Media at Just Global attributes the difference in spend to a shift in newer platforms.

She says: “We’ve seen a definite shift to newer platforms, such as TikTok, in an effort to reach the coveted younger voter demographic. This may not come as a surprise to anyone, but when joining TikTok in June, Republican candidate Donald Trump swiftly attracted millions of followers (up to 6.5 million as of 20 June) compared to Biden’s 382k followers. The irony to me here is that this is the very platform Trump tried to ban while in office on the basis of national security concerns.”

Moseley agreed, adding: “Biden's team will always have an uphill battle to fight on digital as they require pay-to-play reach versus Trump's massive organic audience, which is two-three times the size of the Biden campaign on almost every platform.

“There's signs the Democrats have learnt from the 2020 campaign, where the Trump team took early initiative and went early on digital ad spending to drive donations towards later efforts. Yet there's signs Trump has the advantage here again in 2024 having turned his most recent criminal case into a fundraising effort with his followers.”

Watson’s colleague, Patrick Fenton, VP of Media Strategy, pointed out there is “a lot more to what each candidate’s campaign is doing across media” and drew attention to Trump’s own platform Truth Social and X, formerly Twitter.

“Research also points to Meta platforms being more liberal leaning,” he adds, “and X more conservative, in terms of the type of content users say they see (Pew).”

So what can the industry expect to see in the run up to the elections in November?

Moseley and Watson both agree about personalisation being key, adding that it is “hugely overrated”.

“Ad messaging that is simple, easily repeated and that unites large and disparate groups around common goals (such as abortion rights) can help the nominees land their lead messages instead of wasting money and focus,” Mosely says.

But, he adds: “It's important to note the spending floodgates really opened in the last three months prior to the vote in 2020 so while it's important to see the Democrats starting to spend early ahead of the first presidential debate, the real ramp up will be in the coming months as battle lines are drawn on messaging: it's crucial this is established and tested before wasting money on the wrong lines.”

Premium content editor Jyoti Rambhai

Reporter Reem Makari

Designer Jide Eguakan

Data projects manager Carolyn Avery

The information on this report is correct as of 21 June 2024